I have recently seen a number of articles suggesting that 2016 could in fact be a re-run of 2008. In other words a financial storm is brewing but most of us just don’t realise it, or maybe don’t see it yet. As a manager of my own SIPP (Self Invested Pension Plan – a bit like a 401k if US based) it matters to me. It does to you as well although the distance between you and retirement and the distance between you and your ‘managed’ pension plan probably makes it feel somewhat remote.

I started taking a far greater interest in the movements in world markets about ten years ago. With a background in accountancy I have never really been uncomfortable with numbers, and PE ratios, EPS and dividend cover have been familiar concepts for many years. Alas it’s not really enough if you are going to directly control your own financial health, you really need to gain an understanding of the fundamentals of investing and the dynamics of markets, and possible even an insight into technical trading. I have also found it useful to try and better understand the movements of financial markets work and revisit a number of basic economic theories. On this latter point most economists have been trained in the Keynesian paradigm so the views you tend to get are filtered through Keynes economic theory. Our global banking system is also pretty much managed by Keynes followers so if you can get your head around some basic Keynes principles it is far easier to take a guess at the sort of policies they will follow when conditions change.

Central bankers were mentioned deliberately. In recent years it has become obvious that the markets have reacted, Pavlov style, not just to their policies but even to their ‘jawboning’. A newspaper article by Jim Bullard, a US FED president (St. Louis) can move markets. When the US markets react they frequently influence the European markets, sometimes even more than our own indigenous British or European central bankers. In other words there is a fairly tangible link between a US FED member opining on a local US issue and the value of my SIPP. It therefore makes sense to keep an eye on what is taking place outside the UK, in Europe, China, Japan and US.

The theme of this blog is 2016 vs. 2008. ‘History doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme’ as Mark Twain is often purported to have said. This is also true of 2016 in that the US sub-prime derivative catalyst is unlikely to be the source of any problems later this year. In 2008 many of the US banks had miniscule capital ratios and the regulatory framework severely weakened. This is not the case today in that the US banks are far better capitalised, regulation is somewhat improved and the world of MBSs (Mortgage Backed Securities) is far more controlled. I would also like to think that there have been some cultural improvements in the banking system, although that of course we can’t really know until the next crisis emerges.

I do think that we have to look outside the United States for a catalyst. There are many potential candidates ranging from stability in the Eurozone banking system to Japan or China’s lacklustre economic growth story. It could be one or all of these things interacting with each other or perhaps it will be something taking place in the sovereign bond markets or instability in currencies.

Many of the change, transformation or performance improvement projects and programmes I get involved in involve identifying or improving KPIs (Key Performance Indicators) or what I call OPIs (Operational Performance Indicators), the latter being important but not key indicators. I like to apply this analytical framework to economic conditions and the markets as an aid to helping make decisions on what and where to invest.

The markets are not the economy but there is obviously a link between the two. When you get central banks interfering with markets the link is weakened but not eliminated, a good example being the QE (Quantitative Easing) fuelled extended bull cycle the US S&P has experienced until recent months. Irrespective of these interventions the bankers cannot delay the influence of fundamental economic conditions forever, so it’s useful to work through a number of global indicators to get a sense of context.

World GDP (Gross Domestic Product) is obviously a good ‘world KPI’ but it is limited in that it’s a lag indicator. It is a reasonable measure of what happened last year. More useful KPIs are those that track current activity, and two that I occasionally take a look at are the ‘Baltic Dry’ and the global PMIs (Purchase Managers’ Index).

The Baltic Dry provides a sense of world trade which is something of an analogue for global economic activity. It is not entirely reliable on a historical sense in that the boom years of the early 2000s resulted in an increase in shipping tonnage; in other words an increased supply of ships. Nonetheless, despite this distortion acting as a drag on freight pricing the index is trading at historically low levels. At its peak in 2008 the index exceeded 11,500 while today it has struggled to stay above 350.

Notwithstanding additional capacity, there has still been a massive drop in world trade, particularly in East –West import and exports.

The Markit PMI Index tracks PMI in 30 countries. It tracks output, orders prices and employment metrics and is closely watched as an indicator of forthcoming economic conditions. 50 is set as the benchmark with anything above this level suggesting better times ahead while results below indicates potential recessionary conditions. January 2016 data confirms the bear market in basic materials but still suggests that world financials and technology are still in positive territory. However, performance in in consumer services are showing signs of decline, particularly in the US:

https://www.markiteconomics.com/Survey/PressRelease.mvc/dff621d8de6144f189ab901ce430c809

Which brings me to the US. The US is still the largest economy in the world despite the economic assault of China. Whatever happens in the US economy has set the tone for world activity for decades so it’s a good idea to be knowledgeable about what is happening ‘over there’. There have been some improvements in US conditions in last few years, particularly in U3 unemployment numbers and growth. This could be changing. Notwithstanding retail, housing and car sales holding up there clouds are starting to appear on the horizon.

The US dollar may be (very slowly) fading as the premier currency in the world but it still remains the only option as world reserve and the size of its bond markets underpins its role as a safe harbour in a sea of volatile currencies. The enthusiasm for US dollar in the last couple of years can be seen in the DXY, a measure that tracks its performance against a basket of other currencies. The DXY has rocketed from 80 in 2014 to nearly 100 today:

In other words it has increased in value by almost 25% in a very short space of time. This looks like it may be beneficial to the US but it has a cost. Most of the larger US companies trade overseas and have experienced a drop in earnings as a result of local currency translation into USD. Central banks like to use the currency devaluation tool so the US FED are not likely to be particularly pleased with this situation. Import prices have dropped which means price deflation, another frustration in that the rationale for increasing interest rates is undermined. Long term it’s even worse. US debt is not only heading for $20 trillion but the value of that debt (purchasing power) is not eroding – most central bankers like to increase inflation to 2% or more as a contribution towards reducing its purchasing power. Its nominal value may be increasing but its buying power reduces if you can create ‘healthy’ inflation.

China’s growth is slowly reverting to the lower more ‘normal’ levels experienced by developed economies. It really is too large to generate the double digit growth of the past, especially when the structural impetus is to migrate from a manufacturing into a service based economy. It will be spending less on ghost cities and extravagant infrastructure but there still major initiatives such as the new ‘Silk Road’ which is attracting spend. It needs to eliminate surplus manufacturing capacity but it can’t achieve this overnight, the political risks of a social reaction to industry closures mean that it will take time to restructure.

I don’t really think that the catalyst for the next crisis will be in changing economic conditions, my guess is that it will occur in the markets. Deutche Bank’s $60 trillion derivatives book combined with its low capitalisation rate has recently been cited as a major risk to the European and therefore world banking system. Its president recently had to reassure markets about the robustness of its balance sheet while at the same time going back to the market to raise more capital. Deutche may be a risk but it’s a known risk and doesn’t yet look like the next Lehman. The markets move quickly but it probably deserves a pass at this stage.

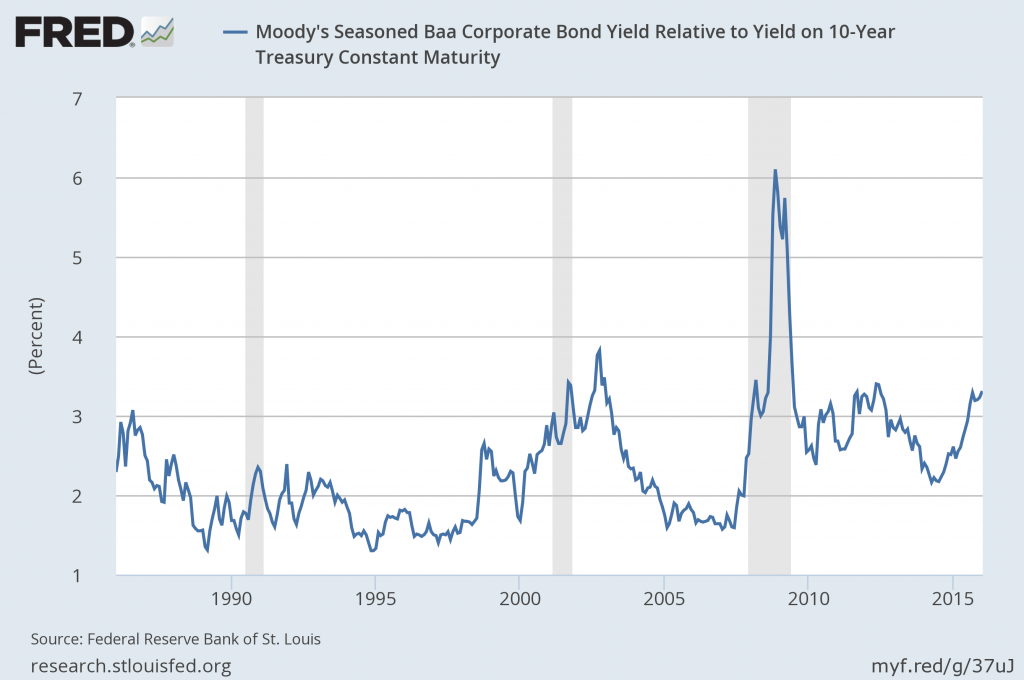

It is the unknown or little publicised risks that are the real concern. Credit spreads, the difference between any bond and a sovereign treasury have widened over the past year. This is a concern. Wider spreads mean growing risk and they are on the rise. We are not yet at 2008 levels but we are close to dotcom bubble levels and seem to be on a clear trajectory upwards. The US FRED charts are a useful tracker, using the benchmark 10 year bond as a reference point:

Liquidity is also an issue in the sovereign bond markets in that the central banks have been buying up government debt across the world at an unparalleled rate. Perversely, the policy of central banks buying up sovereign debt and sucking liquidity out of global markets may in fact become a catalyst for a crisis. Japan’s bond market is one to watch with this in mind.

I believe that gold is really a currency despite the PR of the last forty or fifty years. It still trades as a currency pair and is still stored in the vaults of most central banks as part of a country’s currency reserves. In recent years most central banks outside of the West have been buyers of gold, particularly China, whose gold reserves are officially less than 2000 tons but unofficially estimated at anything up to 30,000 tons.

It is not the price of gold that I track as an indicator but the gold/silver ratio. In the past when the gold/silver ratio has got to 80 or more we have had some form of crisis. In 2008 the ratio hit 83, in other words one ounce of gold bought 83 ounces of silver. Panic in the markets drove investors into gold so its value relative to other commodities rapidly increased to crisis levels. Silver is a form of money as well but it also has an industrial aspect and it’s this aspect that manifests itself when crisis conditions are apparent; gold is the behavioural driver of the ratio.

The worrying point at the moment is that the gold/silver ratio is almost at the 2008 peak:

It closed on Friday at 83.04 vs. the 2008 high of 83.86. If it were the only indicator of stress on the credit markets we would already be in a crisis situation. Fortunately, it is not a widely used indicator and is usually reactive to conditions rather than a driver of behaviour. At the moment I see it as a fear indicator, and perhaps the reaction of disaffected currency holders in nations where negative interest rates reign. Gold is often cited as not paying any interest but it’s a far better investment than a bank account in a world where you have to pay a bank to hold your cash.

So, in summary I don’t see an imminent Lehman type moment but there are concerns both in the fundamentals of economic activity and in some of the market indicators.

2016 may not be 2008 just yet but then again we are only two months into the year, and there is that small matter of a Brexit vote which could make things very interesting in May and June. Volatile markets look like a certainty this year, whether or not associated with a true crisis.